One of the main topics we chose for the CITYMAKERS exchange at its kick-off was urban gardening and farming. At the time, it was you who had explicitly drawn our attention to the fact that this topic is about much more than just a little “urban gardening,” that in view of the challenge of population nutrition, in China in particular, the use of city spaces for agricultural purposes has a lot of potential. In the last 5 years, have you witnessed noticeable and relevant urban farming projects in China? Or models in Europe that are transferable to China? How has this field developed?

My observation is that there are two kinds of urban farming developing in China:

· Educational and recreational projects such as Pan Tao’s Ecoland Club (Schrebergarten project) in Shanghai, rooftop gardening projects and school gardens, all mainly projects by and for urban middle-class people

· High tech greenhouses (hydroponic, LED, aquaponic) for commercial vegetable, flower and mushroom farming. I see great potential in redeveloping unused urban structures („Investitionsruinen,“ such as vacant shopping malls, offices and apartments) for greenhouse/vertical farming development.

One of the main theme in your professional career is that of “environmental protection and education.” For many years you had been [MOU1] building up the Center for Environmental Education and Communication under the Chinese Ministry of Environment in Beijing. How has the landscape in this field changed? Has the approach to environmental education within the Chinese education system (or outside) evolved/matured? Would you say all the German projects have had an influence?

In general, my impression is that environmental awareness has increased, especially among the urban middle class, and that a healthy, green environment has become an element of the quality of life they demand, especially for their children. One also gets the impression that, to a greater extent, the present leadership is building its legitimacy on the improvement of environmental quality. The term “ecological civilization” plays a central role in Xi Jinping‘s philosophy. On the other hand, it is a very autocratic approach, and civil society and NGOs are required to keep a low profile. Based on my observation, between 2000 and 2008, when I was working for the Center for Environmental Education and Communication, part of today’s Ministry of Ecology and Environment, environmental NGOs enjoyed more freedom than they do today.

What further topics do you think are of particular relevance for Sino-European exchange in the field of sustainable (urban) development? For example, what about the issue of water?

I think the issue of climate change is very important. How to adapt future cities to climate change, how to make cities resilient – of course this includes the water issue. Cities need to be better prepared for disasters and rising sea levels. In dry regions, rainwater harvesting and urban greening are very important.

Another relevant topic is the pandemic. At the moment it is not quite clear yet if COVID-19 will have a long-term effect on our cities. If this is the case, and people will work from home more, preferring online conferences to real meetings, this will have a huge impact on the design of cities in the future: no more need for big office towers, hotels or convention centers, but greater demand for bigger apartments with more space for both work and leisure, more areas for open-air meetings, etc.

If you had to suggest a concrete Sino-European CITYMAKERS 2.0. project, regardless of money, time, and any other constraints, what would it be?

A project targeting the challenges of aging societies.

Last year you undertook a commemorative trip (30 years?) through China. Where did you go? Despite the rapid change of the last decades, did you find things that had not changed at all since you first travelled through China? What surprised you most?

Actually, it was a fortieth anniversary trip. In 1979 my friend Kosima and I attended a language course at the Beijing Yuyan Xueyuan. After finishing the course, we travelled for three weeks – to Xian, Chengdu, Kunming and Shanghai. Last year we followed the same itinerary. It was different in terms of:

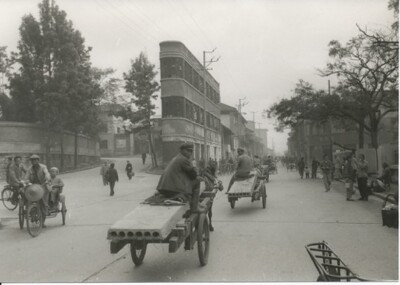

· Speed: Life seemed slow back in 1979. It took us three weeks to travel the four cities by steam train. In 2019 we did it in 9 days on high-speed trains going up to 350 km/h.

· Foreigners: In 1979 people outside Beijing were not used to foreigners, and in many places they would gather and stare at us, but they were very shy and very few dared talk to us.

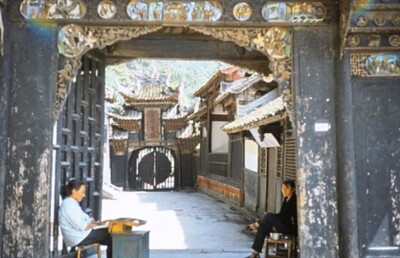

· Loss of local character and culture: Back in 1979 each of the cities we visited had a very distinct character (I remember, for example, the frame houses [MOU2] in the old city of Chengdu). Nowadays almost all of the historic districts are gone and the cities look quite similar.

· Equal societies: Back in 1979 there was not such a clear distinction between cities and the countryside. There were a lot of horse-drawn carts in the cities. Most people were dressed in blue, green or grey outfits. Actually, we also dressed in blue trousers, so we could still tell people in our broken Chinese that we were from Xinjiang (some actually believed us!).

· Development of tourism: Forty years ago we spent a lot of time trying to buy train tickets and negotiating with hotels because most of the places were not allowed to welcome foreigners. Today it’s very easy to buy tickets and reserve hotel rooms. Domestic tourism was almost non-existent in 1979, but now tourist attractions are overcrowded. Some of them (temples, etc.) may seem very old, but are actually modern reconstructions that did not exist in 1979.